Circle of Fifths: Music Theory Guide for Key Relationships and Harmony

1What is the Circle of Fifths

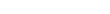

The Circle of Fifths is a visual representation of the relationships between the twelve tones of the chromatic scale. It organizes all major and minor keys by their key signatures, revealing patterns that govern Western music harmony.

Moving clockwise around the circle, each key is a perfect fifth higher than the previous one. Moving counterclockwise, each key is a perfect fourth higher (or a fifth lower). This simple structure encodes profound musical relationships.

Understanding the Circle of Fifths accelerates learning music theory, simplifies transposition, enables smooth modulations, and reveals why certain chord progressions feel natural while others sound jarring.

2Understanding the Structure

Starting at the top with C major (no sharps or flats), moving clockwise adds one sharp per step: G has one sharp, D has two, A has three, and so on until reaching F# with six sharps. The pattern is consistent and predictable.

Moving counterclockwise from C adds flats: F has one flat, Bb has two, Eb has three, continuing to Gb with six flats. At the bottom, F#/Gb are enharmonically equivalent—the same pitch with different names.

Adjacent keys on the circle share six of seven notes. This close relationship makes them naturally compatible for chord progressions, key changes, and harmonic mixing. Distant keys share fewer notes and sound more contrasting.

Memory Trick: The order of sharps (F-C-G-D-A-E-B) and flats (B-E-A-D-G-C-F) are reverses of each other. Memorize one, and you know both!

3Key Signatures Explained

Key signatures indicate which notes are consistently altered throughout a piece. Rather than writing sharps or flats before every affected note, the key signature establishes these modifications at the start of each line.

The Circle of Fifths makes determining key signatures simple. For sharps, count clockwise from C. For flats, count counterclockwise. The number of steps equals the number of accidentals in the key signature.

Sharp keys add sharps in order: F#, C#, G#, D#, A#, E#, B#. Flat keys add flats in order: Bb, Eb, Ab, Db, Gb, Cb, Fb. Knowing these sequences lets you write any key signature from memory.

4Relative Major & Minor

Every major key has a relative minor that shares its key signature. The relative minor is found three semitones (a minor third) below the major key. On the Circle of Fifths, relative minors typically appear on an inner ring.

C major and A minor share zero accidentals. G major and E minor share one sharp. This relationship means relative keys share all the same notes—only the tonal center differs, creating different emotional qualities from identical raw materials.

Understanding relative keys enables smooth transitions between major and minor feels within a song. Many pop songs alternate between relative keys for verses and choruses, creating emotional contrast without jarring key changes.

5Building Chord Progressions

The Circle of Fifths reveals chord relationships within a key. The I, IV, and V chords—the primary chords of any key—sit adjacent to each other on the circle. This adjacency reflects their harmonic closeness and compatibility.

In C major: C (I) sits at top, with F (IV) counterclockwise and G (V) clockwise. These three chords appear in countless songs because their proximity on the circle creates smooth, natural voice leading.

Secondary dominants, borrowed chords, and modulations become logical when viewed through the circle. Moving by fifths creates strong progressions; larger jumps create more distant, dramatic harmonic motion.

6Modulation & Key Changes

Modulation—changing key within a piece—is smoothest between adjacent keys on the circle. Moving from C to G (one step clockwise) feels natural; moving from C to F# (opposite side) is dramatic and challenging.

The pivot chord technique uses chords common to both keys as bridges. Adjacent keys share most diatonic chords, providing many pivot options. Distant keys share fewer common chords, limiting smooth transitions.

Understanding these relationships helps you plan modulations strategically. Step-by-step movement around the circle creates gradual harmonic journeys; leaps create surprise and contrast.

7DJ & Harmonic Mixing

DJs use the Circle of Fifths (often via the Camelot wheel system) for harmonic mixing—transitioning between tracks in compatible keys. Adjacent keys blend smoothly; distant keys clash noticeably.

The Camelot system simplifies this for DJs: each key gets a number (1-12) and letter (A for minor, B for major). Compatible keys are ±1 on the same letter, or same number with different letter (relative major/minor).

Harmonic mixing elevates DJ sets from technical mixing to musical performance. Tracks flow naturally when keys align, creating cohesive journeys rather than jarring genre tours.

8Practical Applications

Use the circle for transposition. To transpose up a fifth, move one step clockwise. Down a fourth, same thing. This beats counting semitones manually and reduces transposition errors.

When learning songs by ear, the circle helps identify likely chords. Most songs use primarily I, IV, and V with occasional vi. Once you identify the key, the circle shows you these chords instantly.

Practice scales around the circle. Playing through all twelve major scales in circle order (C-G-D-A-E-B-F#-Db-Ab-Eb-Bb-F-C) reinforces key relationships and develops comprehensive key familiarity.

Compose using circle movement. Chord progressions that follow the circle (like vi-ii-V-I) feel inevitable and satisfying. Experiment with clockwise, counterclockwise, and skipping patterns for different effects.