1Understanding Frequency Analysis

Frequency analyzers transform audio from the time domain—what we hear as sound waves—into the frequency domain, showing which frequencies are present and at what levels. This visualization reveals tonal content invisible to plain listening.

While trained ears remain the ultimate tool for mixing and mastering, analyzers provide objective data that confirms or challenges what we think we hear. They're especially valuable in untreated rooms where acoustic problems distort perception.

Our browser-based analyzer displays real-time frequency content from your microphone or uploaded files, helping you understand spectral balance without expensive studio analyzers or plugin subscriptions.

2Reading the Spectrum

The horizontal axis shows frequency, typically from 20 Hz (deep bass) to 20,000 Hz (highest audible treble). Human hearing spans roughly this range, though sensitivity varies—we're most sensitive in the 2-5 kHz range where speech clarity lives.

The vertical axis shows amplitude or level, usually in decibels. Taller peaks indicate louder frequencies. The display updates in real-time, showing how frequency content changes moment to moment.

Most analyzers use logarithmic frequency scaling because human pitch perception is logarithmic—each octave doubles in frequency but sounds equally spaced. Linear scaling would compress bass and over-expand treble.

The Pink Noise Reference: Balanced audio often shows a gentle downward slope from bass to treble when analyzed with pink noise. This reflects how we perceive loudness across frequencies—flat measurement isn't flat perception.

3Frequency Range Guide

Sub-bass (20-60 Hz) is felt more than heard. Kick drum thump, bass drops, and earthquake rumble live here. Too much creates mud and uses headroom; too little sounds thin on full-range systems.

Bass (60-250 Hz) carries fundamental weight. Bass guitar, kick body, and low male vocals reside in this range. Proper bass management separates professional mixes from amateur ones.

Midrange (250 Hz-4 kHz) is the most critical range. Vocals, guitars, and most melodic content concentrate here. Clarity, presence, and intelligibility depend on midrange balance.

High frequencies (4-20 kHz) add air, shimmer, and detail. Cymbals, sibilance, and ambient information occupy these frequencies. Too much creates harshness; too little sounds dull and dated.

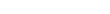

4Mixing Applications

Use analyzers to spot frequency buildups and holes. Multiple instruments occupying the same frequencies create mud—the analyzer shows where energy piles up, guiding EQ decisions about which element owns which space.

Check bass balance across different systems. Bass perception varies dramatically with speakers and room acoustics. Analyzers reveal actual bass content regardless of monitoring limitations, helping you mix confidently.

Compare your mixes to references visually. Aside from training your ears, seeing how commercial releases distribute energy across frequencies provides concrete targets for your own balance.

5Identifying Problems

Resonant peaks appear as narrow spikes that don't move with the music. These might indicate room modes, problematic frequencies in recordings, or equipment issues. Narrow EQ cuts can tame them.

Frequency masking shows when you can see but not hear certain content—other elements obscure it. If your analyzer shows kick drum energy but you can't hear it, the bass guitar might be masking it. Time for EQ carving.

DC offset and subsonic rumble appear below 20 Hz. These waste headroom and can cause speaker damage. High-pass filtering at 30-40 Hz on individual tracks removes this inaudible energy.

6Using Reference Tracks

Analyzing commercial releases in similar genres establishes targets for frequency balance. Professional mixes share general spectral shapes within genres—understanding these shapes guides your mixing decisions.

Level-match your reference and mix before comparing. Louder always sounds better due to psychoacoustic effects. True comparison requires matched loudness, not matched peaks.

Note how references change throughout the song. Verse, chorus, and bridge may have different frequency balances supporting different energies. Dynamic mixing responds to arrangement changes.

7Room Acoustics Analysis

Frequency analyzers help evaluate room acoustics. Play pink noise through your monitors and analyze what the microphone captures. Deviations from flat response indicate room problems at those frequencies.

Bass modes cause narrow peaks and nulls in low frequencies. These room resonances make certain bass notes boom while others disappear. Identifying mode frequencies guides treatment decisions.

Compare analysis from different listening positions. Room acoustics vary with position—the analyzer reveals where frequency response is most accurate for mixing decisions.

8Tips & Best Practices

Don't mix with your eyes. Analyzers inform but shouldn't dictate. Something can look wrong but sound right, and vice versa. Use analysis to guide investigation, not to override ears.

Check analysis with various window sizes. Different FFT sizes reveal different detail—large windows show precise frequencies but blur timing; small windows show transient detail but blur frequencies. Neither is "correct."

Analyze at appropriate levels. Our ears perceive frequency balance differently at different volumes (Fletcher-Munson curves). Mix at moderate levels where perception is most linear.

Use analysis throughout your process, not just at the end. Catching frequency problems early—during recording and tracking—prevents difficult fixes in mixing.