Converting Q Factor to Bandwidth: A Complete Guide for Audio Engineers

Introduction to Q Factor in EQ

The Q factor parameter on parametric equalizers represents one of the most powerful yet often misunderstood controls available to audio engineers. Standing for quality factor, this parameter originates from electrical engineering principles but has become essential vocabulary in modern music production and audio processing.

When you adjust the Q on an EQ band, you are fundamentally changing the selectivity of that filter. A higher Q value means the filter is more selective, affecting a narrower range of frequencies around your chosen center point. This selectivity makes high-Q settings ideal for surgical tasks like removing specific resonances, eliminating feedback frequencies, or notching out problematic tones without disturbing the surrounding frequency content.

Lower Q values create broader, more gentle curves that affect wider frequency ranges. These settings excel at musical tasks like shaping the overall tone of an instrument, adding warmth or brightness to a mix, or making broad tonal adjustments that enhance rather than correct. The wider curve interacts with more frequencies simultaneously, creating results that often sound more natural and musical.

Understanding Q becomes particularly important when working with complex arrangements where multiple instruments occupy similar frequency ranges. Precise Q control allows you to carve out space for each element without creating obvious holes or peaks in the frequency spectrum.

Understanding Bandwidth in Octaves

Bandwidth provides an alternative way to describe the same filter characteristic that Q represents, but using musical terminology that many engineers find more intuitive. Measured in octaves, bandwidth directly relates to how we perceive musical intervals and frequency relationships.

An octave represents a doubling of frequency. When middle A is 440 Hz, the A one octave higher is 880 Hz, and the A one octave lower is 220 Hz. This logarithmic relationship matches how human hearing perceives pitch, making octave-based measurements feel natural when making musical decisions.

When an EQ band has a bandwidth of one octave centered at 1000 Hz, it affects frequencies roughly from 707 Hz to 1414 Hz at the -3 dB points. This range spans the same musical interval regardless of where in the frequency spectrum you apply it, making bandwidth in octaves a consistent way to describe filter width across different center frequencies.

Many graphic equalizers use fixed bandwidth settings, with third-octave equalizers being particularly common in live sound and room correction applications. Understanding how these fixed bandwidths translate to Q values helps when moving between graphic and parametric EQ approaches.

The Conversion Formula Explained

Converting Q factor to bandwidth requires a mathematical formula that accounts for the logarithmic nature of frequency perception. While the formula might seem complex at first glance, understanding its structure helps demystify the relationship between these two ways of expressing filter width.

In this formula, BW represents bandwidth in octaves, Q is the quality factor, asinh is the inverse hyperbolic sine function, and ln(2) is the natural logarithm of 2, approximately 0.693. The formula produces results in octaves, which can then be converted to other units if needed.

For those who prefer working with simpler approximations, a useful relationship to remember is that Q multiplied by bandwidth in octaves approximately equals 1.41 for moderate bandwidth values. This rule of thumb provides quick mental estimates, though the actual relationship curves away from this linear approximation at extreme values.

The inverse relationship between Q and bandwidth becomes clear when examining the formula. As Q increases, the argument to the asinh function decreases, producing smaller bandwidth values. This mathematical relationship confirms the intuitive understanding that higher Q means narrower bandwidth and vice versa.

When to Convert Q to Bandwidth

Several practical scenarios make Q to bandwidth conversion valuable in professional audio work. Understanding when this conversion helps streamlines your workflow and improves consistency across different tools and projects.

Documentation and session notes often benefit from bandwidth descriptions because they communicate more musically to other engineers who might work on the project later. Writing that a cut used a half-octave bandwidth conveys more immediate meaning than specifying Q 2.87, especially to those who think naturally in musical terms.

When matching settings between plugins with different interfaces, conversion becomes essential. Your reference EQ might display Q while your target system shows bandwidth, requiring accurate conversion to achieve matching sonic results. This situation arises frequently when moving sessions between different DAWs or studio environments.

Educational and training contexts also benefit from bandwidth thinking. Teaching concepts like tonal shaping versus surgical EQ becomes clearer when described in terms of one-octave versus quarter-octave bandwidth rather than abstract Q numbers that require additional context to interpret meaningfully.

Finally, when designing custom audio processing or programming your own tools, understanding the mathematical relationship between Q and bandwidth enables you to implement flexible interfaces that can display either parameter based on user preference.

Reference Q Values and Their Bandwidths

Having a mental library of common Q values and their corresponding bandwidths accelerates your EQ decisions. These reference points allow quick translation without calculation, improving your workflow efficiency during mixing sessions.

| Q Factor | Bandwidth (Octaves) | Common Use |

|---|---|---|

| 0.40 | 3.0 | Very broad tonal changes |

| 0.67 | 2.0 | Wide shelving-like curves |

| 1.00 | 1.39 | Musical tone shaping |

| 1.41 | 1.0 | Standard parametric width |

| 2.87 | 0.5 | Focused corrections |

| 4.32 | 0.33 | Third-octave precision |

| 8.65 | 0.17 | Surgical notching |

| 14.4 | 0.1 | Very narrow cuts |

The Q value of 1.41, corresponding to exactly one octave, serves as a particularly useful anchor point. Many engineers use this as their starting point for general EQ moves, widening for more musical adjustments or narrowing for more surgical work as the situation requires.

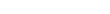

Practical Mixing Applications

In vocal mixing, understanding the relationship between Q and bandwidth directly impacts the naturalness of your results. A common approach uses wider bandwidths (lower Q around 1-2) for presence boosts in the 3-5 kHz range, ensuring the enhancement sounds musical rather than harsh or artificial. Conversely, narrow bandwidths (higher Q around 4-8) work better for removing specific resonances or room modes that color the recording negatively.

Drum mixing benefits similarly from bandwidth awareness. The attack of a kick drum might need a narrow boost around 3-4 kHz to cut through a dense mix, while the body benefits from wider curves in the 60-100 Hz range. The snare drum often needs careful bandwidth choices to add crack without harshness, typically using moderate Q values around 2-3 for mid-frequency presence.

Bass instruments present unique challenges where bandwidth choices significantly affect clarity and definition. Very narrow cuts can remove problematic notes that boom excessively without thinning the overall bass tone, while wider adjustments shape the fundamental character and help the bass sit properly against the kick drum.

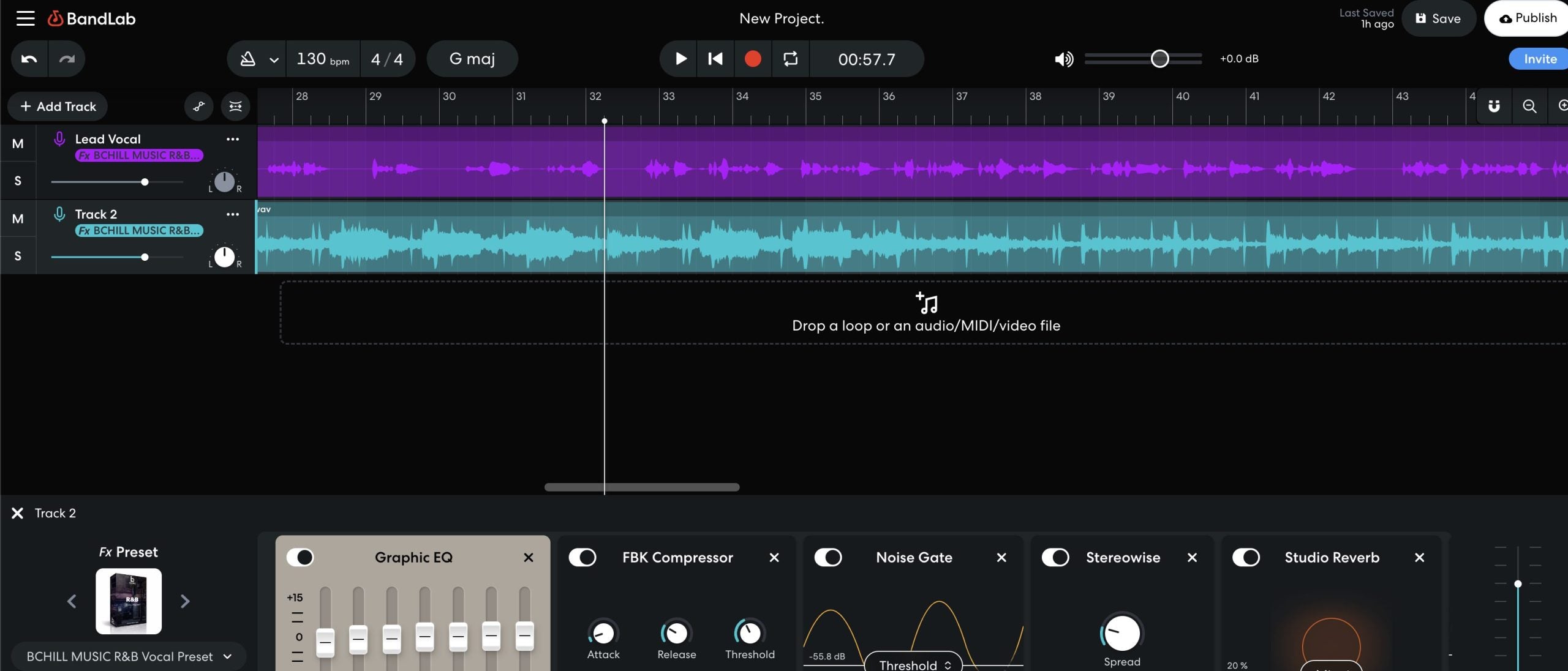

Professional EQ Settings Ready to Use

Our vocal presets include carefully tuned EQ curves with optimal Q settings for different vocal styles and genres.

Explore Vocal PresetsUnderstanding Plugin Differences

Not all EQ plugins implement Q and bandwidth identically, and these differences can affect your results when translating settings between systems. The most common standard defines Q at the -3 dB points of the filter curve, meaning the points where the response has dropped 3 dB from the peak value.

Some vintage-modeled plugins deliberately deviate from mathematical precision to capture the behavior of original analog hardware. Classic Pultec-style EQs, for example, have frequency-dependent Q behavior that changes based on how much boost or cut you apply. API-style EQs use fixed proportional Q that maintains a consistent curve shape regardless of gain amount.

Digital parametric EQs from different manufacturers may also calculate Q slightly differently, particularly at extreme settings. Some constrain Q to prevent very narrow or very wide values that might cause stability issues or produce inaudible results. Understanding your specific tools helps you work within their capabilities effectively.

When precise matching between systems matters, using a spectrum analyzer to compare actual frequency response curves provides more reliable results than assuming identical parameter implementations. The visual comparison reveals any differences in how the tools interpret their settings.

Best Practices and Professional Tips

Developing fluency with Q and bandwidth conversion improves your overall EQ skills and makes you more adaptable across different studio environments. Start by memorizing a few key reference points, particularly the Q of 1.41 equals one octave relationship, and build your mental library from there.

When in doubt, start wider and narrow only if necessary. Broader bandwidths generally produce more natural-sounding results because they avoid the phase anomalies and unnatural resonances that very narrow settings can create. Reserve high-Q surgical work for genuine problems rather than routine tonal shaping.

Consider the musical context when choosing bandwidth. A solo instrument can handle narrower, more aggressive EQ because there are no other elements to interact with. In a full mix, wider bandwidths often work better because they create changes that blend more naturally with surrounding elements.

Pay attention to how bandwidth affects the perception of EQ amount. A 3 dB boost spread across two octaves sounds much different than a 3 dB boost concentrated in a quarter octave, even though the peak gain is identical. The wider boost often sounds like more overall change despite affecting frequencies more gently.