Tempo Sync LFO Calculator: Frequencies for Musical Modulation

Understanding Low Frequency Oscillators

A low frequency oscillator, commonly called an LFO, generates periodic waveforms at frequencies below the audible range, typically from a fraction of a hertz to around 20 Hz. Rather than producing sounds we hear directly, LFOs modulate other parameters to create movement, rhythm, and evolving textures in synthesizers and effects.

LFOs form the foundation of many classic synthesizer sounds and effects. Vibrato uses an LFO to modulate pitch. Tremolo applies LFO modulation to amplitude. Wah effects result from LFO modulation of filter cutoff frequency. Understanding how LFOs work enables you to create and customize these effects intentionally.

The frequency of an LFO determines how fast the modulation cycles. A 1 Hz LFO completes one full cycle per second, creating relatively slow movement. A 10 Hz LFO cycles ten times per second, producing faster, more rhythmic effects. Very slow LFOs below 0.1 Hz create gradual evolution over many seconds.

Tempo-synced LFOs align their cycling with your project tempo, ensuring that modulation effects lock to the beat. This synchronization is essential for rhythmic production styles where wobbles, pulses, and filter sweeps must groove with the music rather than drift against it.

LFO Waveform Types

Different LFO waveforms produce different modulation characters. Understanding each waveform's shape helps you choose the right one for your intended effect and predict how it will affect the modulated parameter.

| Waveform | Character | Common Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Sine | Smooth, continuous | Vibrato, gentle tremolo, subtle movement |

| Triangle | Linear rise and fall | Panning, filter sweeps, pitch modulation |

| Sawtooth | Gradual rise, instant reset | Filter sequences, rhythmic builds |

| Square | Instant alternation | Gating, hard tremolo, trance gates |

| Sample & Hold | Random steps | Arpeggiated effects, glitchy modulation |

Sine waves produce the smoothest modulation because they have no sharp transitions. The parameter being modulated moves continuously between its minimum and maximum values following the gentle sine curve. This smoothness makes sine LFOs ideal for musical effects like vibrato where abrupt changes would sound unnatural.

Square waves create the most abrupt modulation, instantly jumping between minimum and maximum values. This produces rhythmic gating and chopping effects. The duty cycle of a square wave can be adjusted to change how long the modulation stays at each extreme.

Sawtooth waves ramp gradually in one direction then reset instantly. This asymmetric shape creates different effects depending on polarity. A rising sawtooth gradually opens a filter then snaps it closed, while a falling sawtooth does the opposite.

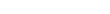

Tempo Synchronization Principles

Tempo synchronization locks LFO speed to musical note values rather than absolute frequencies. When synchronized, a quarter note LFO always completes one cycle per beat regardless of whether your project runs at 80 BPM or 160 BPM. This automatic adjustment keeps modulation effects musically appropriate at any tempo.

Note value divisions work the same way for LFOs as for other tempo-related parameters. A whole note LFO takes four beats to complete one cycle. A sixteenth note LFO completes four cycles per beat. Dotted and triplet values provide additional options between the standard divisions.

The relationship between LFO frequency and tempo follows a simple formula. LFO frequency in Hz equals BPM divided by 60 multiplied by the note division factor. For a quarter note at 120 BPM: 120 divided by 60 equals 2 Hz. For a sixteenth note at the same tempo: 2 multiplied by 4 equals 8 Hz.

Phase alignment determines where in its cycle the LFO starts when playback begins or when a note triggers. Some synthesizers and effects reset LFO phase on note triggers, ensuring consistent attack character. Others free-run continuously, creating more varied results depending on when notes occur.

LFO Frequency Calculations

Calculating exact LFO frequencies enables precise matching of modulation rates between different instruments and effects, even when some use tempo sync and others require manual frequency entry. These calculations bridge the gap between musical and technical parameter systems.

For standard note values at 120 BPM, common LFO frequencies are: 1 bar equals 0.5 Hz, half note equals 1 Hz, quarter note equals 2 Hz, eighth note equals 4 Hz, and sixteenth note equals 8 Hz. These values scale linearly with tempo, so at 60 BPM all frequencies are halved, at 240 BPM all are doubled.

Period, the inverse of frequency, expresses how long one LFO cycle takes. Period in milliseconds equals 60000 divided by BPM for a quarter note, or more generally 60000 divided by BPM multiplied by beats per cycle. A quarter note at 120 BPM has a period of 500 milliseconds.

Some effects and synthesizers display LFO rate as period rather than frequency. Converting between them is straightforward: frequency equals 1 divided by period in seconds, or 1000 divided by period in milliseconds. A 500 millisecond period equals 2 Hz.

Extreme LFO rates push into different perceptual territories. Very slow LFOs below 0.1 Hz create gradual evolution over 10 or more seconds. Fast LFOs approaching 20 Hz begin creating audible sidebands and ring modulation effects rather than perceived movement.

Synthesizer Applications

Synthesizers use LFOs as primary modulation sources for creating expressive, evolving sounds. Understanding common LFO applications in synthesis helps you design patches that respond musically and produce desired timbral effects.

Pitch modulation via LFO creates vibrato when applied subtly and more dramatic effects at higher depths. Typical vibrato uses a sine wave LFO at 5-7 Hz with just a few cents of pitch deviation. Slower rates create pitch wobbles characteristic of certain synthesizer styles. Very slow modulation produces gradual detuning effects.

Filter cutoff modulation produces the classic synthesizer wobble sound. A tempo-synced LFO moving the filter cutoff creates rhythmic timbral changes that lock to the beat. This technique forms the basis of dubstep bass sounds, trance leads, and countless electronic music textures.

Amplitude modulation via LFO produces tremolo effects. At slow rates, this creates gentle volume undulation. At faster tempo-synced rates, it produces rhythmic gating. Square wave LFOs create hard gates while sine waves produce smoother pumping effects.

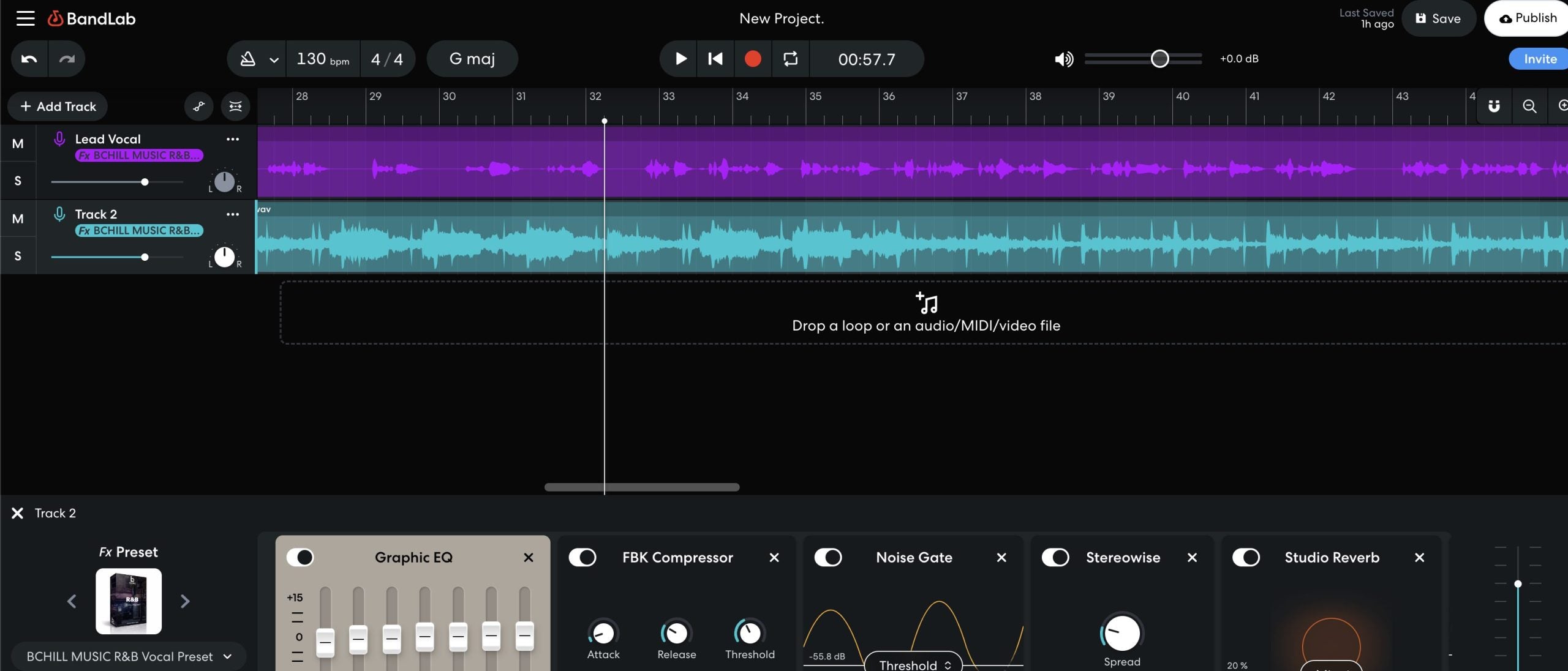

Professional Vocal Processing

Our vocal presets include carefully tuned modulation effects with optimal LFO settings for different styles and applications.

Explore Vocal PresetsEffects Processing Applications

Beyond synthesizers, LFOs drive many common audio effects. Understanding the LFO component in these effects helps you customize them effectively and troubleshoot when they do not lock to your groove as expected.

Chorus effects use LFOs to modulate delay time, creating the subtle pitch variations that produce the characteristic thickness and movement. Typical chorus LFOs run around 0.5-3 Hz with very short modulated delay times. Slower rates produce more obvious movement while faster rates increase shimmer.

Flanger and phaser effects similarly depend on LFO modulation but with different underlying mechanisms. Flangers modulate short delays to create comb filtering sweeps. Phasers modulate all-pass filter stages. Both typically use sine or triangle LFOs for smooth sweeping motion.

Auto-pan effects use LFOs to move sound between left and right channels. A sine wave LFO produces smooth circular panning. A square wave creates hard left-right switching. Tempo-synced auto-pan can reinforce rhythmic patterns or create call-and-response effects between speakers.

Tremolo pedals and plugins use amplitude-modulating LFOs. The rate control adjusts LFO frequency while depth controls modulation amount. Vintage tremolo effects often used specific waveforms and rate ranges that contribute to their characteristic sounds.

Creative LFO Techniques

Creative application of LFOs extends far beyond standard modulation effects. Experimental techniques using unusual rates, destinations, and combinations can produce unique textures and behaviors that distinguish your productions.

Cross-modulation uses one LFO to modulate another LFO's rate or depth, creating complex evolving patterns. A slow LFO modulating a faster LFO's rate produces acceleration and deceleration effects. This technique generates organic movement that simple single-LFO setups cannot achieve.

Polyrhythmic LFO combinations use different rates that do not share common factors, creating patterns that cycle through many variations before repeating. An LFO at 3 Hz combined with one at 5 Hz produces a combined pattern with a 15-beat cycle, far more complex than either alone.

Unusual modulation destinations reveal new possibilities. LFO modulation of reverb size creates breathing spatial effects. Modulating compression threshold produces rhythmic dynamic changes. Modulating EQ frequency sweeps specific bands in tempo with the music.

Sample and hold LFOs create stepped random values, useful for generative sequences and glitchy effects. Syncing sample and hold to tempo produces new random values on each beat or subdivision, creating constantly varying but rhythmically locked modulation.

Advanced Applications and Integration

Advanced LFO applications integrate modulation deeply into production workflow, using calculated frequencies and precise synchronization to achieve effects that would be impossible with approximate settings.

Sidechain-style effects can be created using tempo-synced LFOs instead of actual sidechain compression. A quarter note sawtooth LFO modulating volume produces the pumping effect without requiring a kick drum trigger. This approach offers more control over the pump shape and timing.

Tempo-synced LFO frequencies can match or relate to delay times for interesting interactions. An LFO modulating a parameter at the same rate as your delay time creates synchronized movement. Offset relationships produce more complex polyrhythmic interactions between the modulation and echoes.

Automation of LFO parameters during a track creates evolving modulation effects. Gradually increasing LFO rate builds energy toward a drop. Changing waveform shape during a breakdown creates textural transitions. These automations make static LFO effects more dynamic and arrangement-aware.

Multiple LFOs at related mathematical rates create coherent but complex modulation. Rates in octave relationships (2:1, 4:1) stay phase-aligned. Rates in fifth relationships (3:2) create patterns that realign every few bars. Understanding these relationships enables intentional design of polyrhythmic modulation schemes.