Most songs today start as a stereo “2-track” beat. That’s great for speed—but a single mixed file leaves you little room to carve space for the voice. This guide shows how to place a lead vocal on top of a finished beat so it feels clear, loud, and locked to the grid, without killing the producer’s vibe. You’ll learn fast prep, surgical EQ moves, smart sidechain tricks, timing fixes, mix-bus discipline, and export habits that translate anywhere.

I. What makes 2-track vocal mixes tricky (and how to win anyway)

A 2-track beat already has its own EQ curves, compression, and limiting. When you drop a vocal in, you’re mixing against a “mastered mini-mix.” The fixes are simple in concept:

- Control the beat’s low-end and midrange just enough that the vocal can sit forward.

- Shape the voice cleanly so consonants read without harshness.

- Use ducking, not brute force, to open space moment-to-moment.

- Keep timing tight so phrasing sits on the groove—not in front or behind it.

- Leave headroom so final loudness is punchy, not brittle.

II. Session prep: get the beat and grid right

Set tempo and key. Detect or tap the tempo, then confirm with a quick loop of the hook. If the beat drifts, create a tempo map (bar-by-bar) so edits and delay times line up. Note the musical key if you’ll use pitch correction.

Trim and align the beat. Cut silence before the first transient. Nudge until the first downbeat lands exactly at bar one. If there’s a pickup, place it intentionally (for example, start at bar 0 or add a count-in marker).

True-peak check. If the beat is hot and clipping your headroom, trim its gain—not the master. Drop it 3–6 dB so your vocal chain can breathe. Avoid turning the monitor knob to “fake” headroom; change the file’s or channel’s gain.

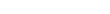

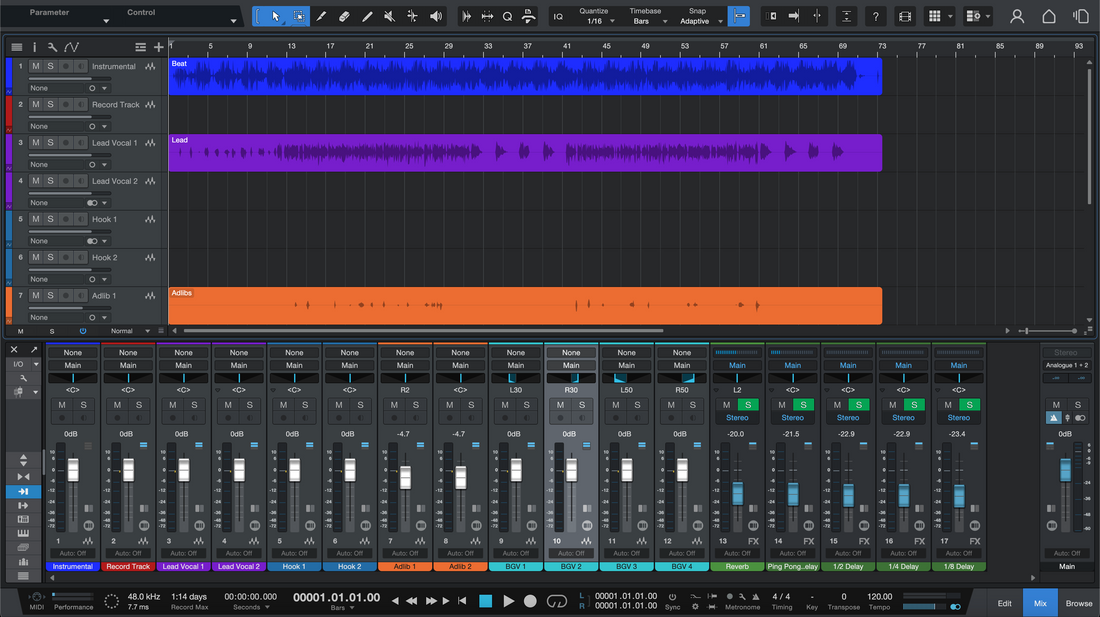

Color and name your lanes. Lead, Double L, Double R, Ad-libs, Harmonies. Group them to a Vocal Bus so you can process the voice as one instrument later.

Low-latency headphones. Track at a small buffer and keep heavy look-ahead plugins bypassed while recording. Give the singer a simple cue mix: beat a bit lower than the vocal, small plate reverb, very light slapback. The goal is confidence, not final FX.

III. Carve the beat without wrecking it

You can’t dissect a stereo file into kick, snare, and keys—but you can shape ranges that matter to lyrics. Think “micro-surgery,” not “tone transplant.”

- Sideband low-end control. Insert a high-quality EQ or dynamic EQ on the beat. Apply a gentle high-pass around 25–35 Hz and a small, wide cut around 50–80 Hz if the subs bully the vocal bus compressor. Keep it subtle.

- Midrange pocket for words (1.5–4 kHz). Sweep to find the beat’s bright edges (hats, synth glare). A narrow 1–2 dB cut that only reacts when those elements spike can reveal consonants without thinning the beat. Dynamic EQ shines here.

- De-mask the “boxy” zone (200–400 Hz). If the beat is thick, try a gentle, wide dip so the vocal chest doesn’t fight guitars/keys. Go small—often 1–2 dB is enough.

- Mid/Side touches. If hats or stereo synths smear the lyric, tuck a dB or two from 3–6 kHz on the Side channel only. Keep the Mid intact so the beat stays strong in mono.

- Don’t stack limiters on the beat. Extra limiting flattens movement and makes vocal ducking pump. Use gentle trims and dynamic EQ instead.

IV. Build a vocal chain that reads at any volume

This starting chain is conservative, fast, and works across mics and voices. Adjust by a dB or two rather than reinventing it every track.

- High-pass filter. Start between 70–100 Hz to clear rumble. If the voice is very deep, lower the cutoff; if proximity is heavy, go a touch higher.

- Subtract first. Sweep 200–400 Hz for boxiness and remove only what’s needed. If upper mids bite, notch the worst resonance gently (1–2 dB, narrow Q).

- Presence and air. Add a small, focused lift around 2–5 kHz for diction. For sheen, a very modest shelf at 10–12 kHz. After each boost, re-check sibilance.

- Leveling compressor. Aim for 2–6 dB of gain reduction on peaks. Use a slower attack (so consonants “speak”) and a medium release (so phrases breathe). If the voice is jumpy, run two light compressors in series instead of one heavy clamp.

- De-esser. Target 5–8 kHz. Keep it event-driven—esses tuck back only when they occur. If brightness fades, you’re over-de-essing.

- Optional saturation. A touch of tape/tube on the Vocal Bus can thicken the midrange so you need fewer EQ boosts. Keep it subtle; you’re mixing into a pre-compressed beat.

V. Make it loud without fighting the beat

A classic mistake is turning the lead up until it masks the beat, then raising the beat, then the vocal again. That arms race kills punch. Let the beat “get out of the way” only when the voice speaks.

- Wideband sidechain ducking. Put a compressor on the beat, keyed from the lead vocal. Use a gentle ratio and 1–3 dB of reduction, with fast attack and quick but musical release (e.g., 80–150 ms). The beat breathes between phrases.

- Mid-band ducking for extra clarity. If the beat’s upper mids are crowded, use a multiband or dynamic EQ on the beat keyed from the vocal, ducking only 2–5 kHz. Words pop; kick and bass stay untouched.

- Ducked delays and verbs. On the FX returns, sidechain from the lead so tails bloom after syllables. You’ll keep intelligibility while sounding bigger.

- Mix-bus discipline. Leave a couple dB of headroom on the master. A safety limiter for roughs is fine, but heavy limiting too early makes the ducking pump. Get the balance right first.

VI. Timing: keep it on-grid and in the pocket

Align the take. After comping, slip the first phrase so it starts on time with the grid or the groove (if the beat swings). For push-or-pull styles, place a single reference consonant (like a “t”) exactly where you want it, then match the rest to that feel.

Double discipline. Hard-panned doubles should support the lead, not compete. Slip-edit consonants so they land together. Keep doubles 6–10 dB lower than the lead and reduce S sounds on doubles more aggressively than on the lead.

Ad-libs and stacks. Place ad-libs in the holes or across bar lines so they feel like answers, not overlaps. Group harmonies to a bus and treat them as one pad you can ride under hooks.

Delay timing. Set delays to song tempo (eighth, dotted eighth, quarter). If the performance rushes or drags, nudge delay time a percent or two to feel “locked.”

VII. Space that flatters the lyric (without smearing it)

Reverb and delay are where most 2-track vocal mixes get muddy. The trick is to make space feel present when the singer stops, not while they’re talking.

- Short plate + slap. A 0.7–1.2 s plate for polish and a low, mono slap for body keep vocals near the listener. Use high-pass and low-pass on both returns.

- Stereo delays for choruses. Dual delays (quarter on one side, eighth on the other) add size to hooks at low levels. Sidechain them so words stay crisp.

- Early reflections over long tails. If the beat already has wide synths or wet keys, use early reflections or a tiny room instead of a long hall. You’ll add depth without fog.

- FX automation. Throw delays on end-words, not mid-lines. Automate verb send up between phrases for drama, down during words for clarity.

VIII. Troubleshooting & fast fixes

- Lead feels small unless it’s too loud. Add a dB of 2–4 kHz presence on the vocal bus, not just the track. Then use mid-band ducking on the beat keyed from the lead (2–5 kHz). You’ll gain cut without fader wars.

- Esses hurt after adding “air.” Back off the shelf, then de-ess around 5–8 kHz. If cymbals now poke through, tame 6–8 kHz on the beat’s Side channel by 1 dB.

- Beat collapses when you duck it. You’re over-compressing. Reduce ratio/threshold or switch to a narrow keyed band (2–5 kHz) instead of wideband ducking.

- Mono compatibility is ugly. Kill chorus/haas tricks on doubles and FX. Let panning and level do the width; keep the lead mono-compatible.

- Vocal dull after heavy de-ess. Use event-driven de-ess only; add a tiny shelf back at 10–12 kHz. Consider a gentle exciter on the bus if the mic is dark.

- Hook feels smaller than the verse. Increase send to dual delays on hooks, widen doubles slightly, and lift the beat with 0.5–1 dB at 120–200 Hz. Tiny, targeted moves beat one big limiter push.

- Beef without mud. Add 120–200 Hz with a wide bell on the vocal bus if the beat’s low mids are already tucked. Otherwise, carve the beat first.

IX. Advanced / pro moves that separate roughs from records

- Vocal Bus “core.” Route Lead, Doubles, and BGVs into a Vocal Bus and make your gentle tone/level decisions there. Keep per-track EQ mostly subtractive; add character on the bus so the stack sounds like one instrument.

- Dynamic split band on the beat. Use two narrow dynamic bands keyed from the vocal—one at ~250–350 Hz (mud share) and one at ~2–4 kHz (diction share). Each moves 1–2 dB only when the voice needs room.

- Harmonic “pin” for presence. Instead of big boosts, add a touch of harmonic saturation focused in the 2–5 kHz band on the vocal bus. This can “pin” the voice in front without brittle EQ.

- Clip-safe loudness. If you need competitive level for the client, use a gentle clipper then a limiter on the mix bus, in that order, and only after balances are set. If cymbals fizz, you’re pushing too far.

- Arrangement fixes. If words fight a hi-hat pattern, automate a tiny dip in hat level (via multi-band on the beat) during phrases. Micro-arrangement beats macro-EQ every time.

- Print stems for mastering. When the 2-track fights a standard stereo master, print a few extra stems (Vocal, Beat, FX) so a mastering engineer can nudge relationships without remixing.

X. FAQs

Should I EQ the beat or the vocal first?

Start with subtractive EQ on the vocal, then carve the beat where it masks. Finish with small, dynamic moves on the beat keyed from the lead—these open space without changing the beat’s vibe.

How loud should my vocal be?

In dense hip-hop/pop, the lead often ends up 1–2 dB above the beat’s midrange energy on your LUFS short-term meter during lines. Trust your ears: vocals should feel in front at low volume and not scream at high volume.

Do I need two compressors?

Not always. Many voices behave with a single, well-timed compressor. If the performance is jumpy, two light stages (leveling → peaks) sound smoother than one heavy clamp.

What delay times work best?

Eighth or dotted eighth for verses; add a quarter in choruses for width. Keep repeats low and filtered. Duck returns from the vocal so lyrics stay clean.

Can I make a stereo beat feel more dynamic?

Yes—use keyed ducking, automated EQ notches, and small arrangement-style moves. Avoid stacking limiters on the beat; they flatten punch.

What if my vocal sounds thin?

Check 200–400 Hz cuts first—maybe you removed too much. Add a dB or two at 120–200 Hz on the vocal bus if the beat leaves room. If not, carve the beat there instead.

XI. Wrap-up (and a faster way to start)

Mixing vocals over a 2-track beat is all about control in small doses. Carve a pocket for words, level the performance without killing energy, and let sidechain-driven moves open space only when the singer needs it. Keep headroom all the way to export. Do that, and your mixes will sound clean, loud, and on-grid—without fighting the beat that inspired the track in the first place.

If you want to skip setup and record into a layout that already routes vocals, buses, and returns the “mix engineer” way, grab our recording templates. Ready to have a pro finish the job? Book our mixing services and send your session—we’ll deliver a release-ready mix and stems you can reuse for shows and remixes.